The Purchasing Power of Ancient Coins

Posted by Andrew Adamo on Jul 3rd 2024

The Purchasing Power of Ancient Coins

Purchasing power is the quantity of goods and services that can be bought with a specific amount of currency. It reflects how much value a currency holds over time. Purchasing power in ancient coins refers to the amount of goods and services that could be acquired with these coins during their time of circulation. For instance, in ancient Rome, a silver denarius was a common currency used for everyday transactions. With a single denarius, a Roman citizen could purchase a day's worth of bread or pay for a modest meal. In comparison, the purchasing power of a denarius today would be vastly different due to changes in the value of money, inflation, and economic development. This historical perspective shows how the value and purchasing power of currency evolve over time.

A question that has often been asked about the ancient coinage of Greece and Romeis what its purchasing power was at the time the ancient coins were issued and how that compares with the purchasing power of ancient coins today.

This is not an easy question to answer, even for researchers on ancient coinage. The starting point for this discussion is to understand that these kinds of comparisons are very difficult to make, especially in exact terms, because they often involve comparing things that are not comparable.

The main problems are that surviving records of wages and prices in ancient times is spotty at best, and second because few of the items that an average Roman purchase dare still commonly purchased items today apart from food staples like bread.

But bread played an even larger role in diets back then when it was inexpensive and people consumed more of it each day, two pounds of it per adult male a day in fact.

Third, prices and wages varied throughout the various parts of the Roman empire.

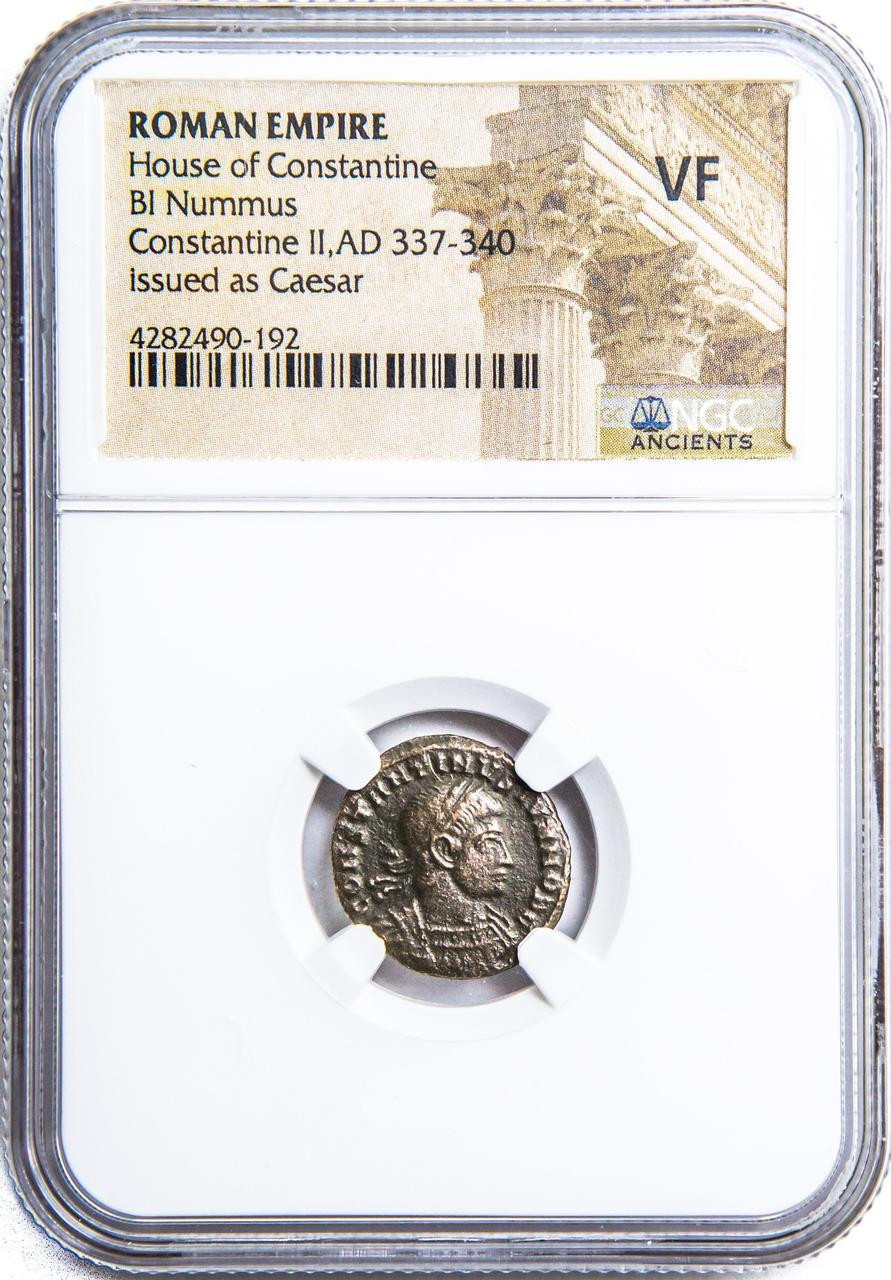

Roman AE of Constantine II (AD 316-340) NGC Wood Box (VF)

Shop all Ancient Roman Coins here >

Ancient world vs. modern times

What is the current value of a U.S. dollar when compared to ancient currencies?

To address this question, those who study this field look at what could be purchased with different denominations of bronze, silver and gold coinage back then. This too is not easy to determine since ancient writers who might have discussed such matters in detail in fact rarely did so because they were mostly privileged elites who saw money as a vulgar topic. This helps explain the poor records on these issues that exist today.

But it is important to try to make these comparisonsbecause ancient money, unlike modern fiat money, is basically “commodity money” that determines value based on the supply and demand of the precious metals in the coins.

Modern currency is instead valued by the government that issued the money. It is based completely on the willingness of people to accept it rather than its intrinsic value.

Bullion equivalent value

One way of trying to understand what could be purchased in ancient times with their coinage is to consider it in terms of bullion value, or the value of the precious metal in silver and gold coins of the period.

For example, a 7-gram ancient Greek gold stater (a very popularcoin that sets the collectors today back thousands of dollars due to numismatic premium) that was issued in the time of Alexander the Great would be about $512, An 8-gram Roman gold aureus from the period of the Julius Caesar has about $585 at today’s gold price.

As for silver coins, they were almost pure at the time rather than alloyed with other metals like copper as they have been in modern times to make them harder for use in commerce. The silver in an Athenian tetradrachm (the most important ancient trading coin in the Mediterranean area for centuries and probably the most popular ancient Greek coin) would be about $14.50.

But using “bullion equivalent value” of ancient coins to try to determine their purchasing power at the time is not a very good way to make this comparison over centuries of human history. For one thing, in ancient times mining gold required a great deal of slave labor, including refining the metal in charcoal-fired furnaces as opposed to modern gold mining that use lots of heavy equipment and technology.

Labor equivalent value

A better way to look at the issue might be to consider labor equivalent value, or how much a typical worker would receive for a day’s work in the coinage of the time.

For example, we know today from many sources that a silver drachma in ancient Greece or a Roman silver denarius were the wage a typical minimum wage worker would have received at the time.

Two Greek Drachmai Half Notes Banknote Folder

In general, in ancient times bronze coins that were of the lowest value were used to purchase daily necessities like bread; silver coins were typically used for wages; and gold coins were used by the elites to buy slaves and luxury goods.

But again, there are limits to each way of comparing. In this case, we are limited by the fact that labor played a much larger role in ancient economies compared to modern ones that use machines and technology to an increasing extent.

Soldier’s pay

A third way to approach the purchasing power question is to look at the pay of soldiers in the ancient world. In the 4th century B.C., Greek hoplites (which were armored infantry) typically were paid a silver drachma per day, sometimes with a second drachma to cover the cost of a servant while they are on military campaigns. If computed into an annual salary, this was the equivalent of receiving 1,540 grams of silver of 103 grams of gold per year.

As for Roman soldiers, they were paid 225 denarii per year in the 1st century B.C., which was raised to 300 denarii under emperor Domitian. That would amount to 972 grams of silver or 64.8 grams of gold. This shows that Greek soldiers were clearly paid better.

If one then considered the modern U.S. soldier’s pay and converted it into silver and gold, we find that they are paid much better than either ancient Greek or Roman soldiers.

Other records show that a Roman legionary soldier was paid 3 asses per day. The as was equal to 1/16th of a denarius, the primary silver coin of ancient Rome.

This enabled him to buy enough bread for a whole year with the pay he received in two months. Prices of goods at the time tended to remain stable with wages, which keeps inflation down.

Currency devaluation

During the latter part of the Roman empire in the 3rd century B.C., there was runaway inflation that not only impoverished many people but also ruined the faith that Romans had in their currency.

To address this economic mess, in the 4th century Diocletian thought that he could simply issue wage and price edicts to make wages and prices fall in line throughout the Roman empire. This did not work well in the 1970s either when there was rampant inflation, and the Nixon administration tried price and wage controls.

Diocletianissued an “Edict on Maximum Prices,” recalling the old coinage and issuing a new denomination known as a Nummus or follis. It was supposed to have the purchasing power of the denarius of the Roman Empire.

He alsocreated a new unit called a denarius communis or d.c. and a new, high quality silver coin called an argenteus worth 100 d.c. was issued along with a gold aureus worth 1,200 d.c.

But the effort failed miserably, and the edicts became unenforceable and were eventually ignored.The new coins continued to lose purchasing power and were debased to reflect the change.

An earlier devaluation took place in 214 A.D. with the introduction of the antoninianusthat was supposed to be worth two denarii, but its actual purchasing power was closer to that of one denarius. The new coins were 50% heavier but the extra weight came from alloy, which meant the silver content of the debased coins was about the same as that of the coins from the earlier part of the 3rd century.

Another example is the Roman sestertius, which was originally a small silver coin during the Roman Republic, but later evolved into a large bronze coin that was equal to 1/4th of a denarius, as it was devalued over time.

Conclusion

On the one hand, ancient economies like those of the modern world were subject to the vicissitudes of economic cycles of boom and bust. In other words, they too had to deal with inflation, recession and in some cases such as under Diocletian with devaluation of a currency’s purchasing power and debasement of its currency.

On the other hand, it appears that inflationgenerally was better contained in the ancient worldcompared to the modern world. And the relatively greater success at containing inflation in the ancient worldprobably has a lot to do with the fact that their money (especially in the earlier centuries) was based on its intrinsic value much more than on the faith and credit its citizens had in the currency.

Finally, more so than for ancient silver coins, the relative purchasing power of ancient gold coins has remained rather stable over time because of their high intrinsic value.

References:

Coin Week

Forum Ancient Coins

FAQ

What is purchasing power?

Purchasing power is the quantity of goods and services that can be bought with a specific amount of currency. It reflects how much value a currency holds over time. For example, $1 in the 1950s could buy significantly more than $1 today, indicating that the purchasing power of the dollar has decreased due to inflation. Understanding purchasing power helps measure the real value of money and its impact on consumer behavior and economic decisions.

What was the purchasing power of ancient Roman coins?

The purchasing power of ancient Roman coins varied significantly over time due to inflation, especially during the later Empire. For example, during the early Empire, a silver denarius might have bought a soldier's daily food ration. To put it into perspective, the purchasing power of ancient coins like the denarius was substantial enough to cover daily necessities but fluctuated with the economic conditions of the time.

How does the purchasing power of ancient Greek coins compare to modern money?

Comparing the purchasing power of ancient Greek coins, such as the drachma, to modern money is complex due to differences in economic systems and available goods. However, it's estimated that a drachma in classical Athens could buy several loaves of bread. This comparison helps us understand the relative value of ancient currencies in terms of basic goods, even if direct comparisons to modern money are challenging.

Can the purchasing power of ancient coins be accurately converted to today's currency?

Accurately converting the purchasing power of ancient coins to today's currency is difficult because of the vastly different economic contexts, including the types of goods available, production methods, and societal needs. However, historians and economists use various methods to estimate this, often by comparing the cost of basic commodities like food and clothing across different periods.

What factors influenced the purchasing power of ancient coins?

The purchasing power of ancient coins was influenced by several factors, including the metal content of the coins, the stability of the issuing government, inflation rates, and the overall health of the economy. For instance, debasement of coinage (reducing the precious metal content) could lead to inflation and decreased purchasing power, as seen in the later Roman Empire.

How did the purchasing power of ancient coins affect daily life in ancient civilizations?

The purchasing power of ancient coins had a significant impact on daily life in ancient civilizations, determining what individuals could afford, from basic necessities to luxury items. It influenced social structures, trade, and economic stability. For example, in ancient Rome, the distribution of coinage and its purchasing power played a crucial role in both urban and rural economies, affecting everything from military logistics to food distribution.