Trade Dollars: A Great Success Abroad but Not at Home

May 27th 2022

Trade Dollars History

In the 1850s as a result of the discovery of large gold deposits in Western states and Australia, the price of gold declined due to the ample supply of the yellow metal available for coinage. Meanwhile, following the discovery of even larger silver deposits, especially Nevada’s Comstock Lode in 1859, in the 1860s the price of silver became distorted by its abundance and declined in price.

At the same time, trade between the United States and China was increasing. Chinese merchants preferred to be paid in Mexican silver pesos minted from 1824 that were the successor to the Spanish pieces of eight issued from 1535. This meant that American exporters had to purchase Mexican pesos to send abroad, which incurred a lot of broker fees, including a 12% excise tax from 1867. Plus, the Mexican coins were worth a premium of 2 to 22% over American silver dollars of the time – the Seated Liberty coins – which were smaller and contained less silver.

Rational for coin

A coin was needed that would address two problems: the need for a trade coin to facilitate commerce with the Far East and “to provide a steady market for the ever-increasing production of silver from the Comstock Lode, and to give relief to American merchants from high premiums and excise taxes,” as Eric Brothers wrote in a February 2022 article in The Numismatist.

When Mexico began in 1866 during the reign of Emperor Maximillian to alter the designs of its coin to include a portrait of the new emperor, the new Mexican coins with the balance-scale motif were unfamilair and not well accepted in China. This provided an opening to offer the Chinese a new silver coin for trade.

Keep in mind that prior to the 1860s the U.S. was regularly importing huge amounts of silver for coinage production, but from that period forward the situation changed greatly. And even going back to the 1780s, silver had been the main U.S. export to China.

In the fall of 1872, Louis A. Gannett, who was treasurer and assayer at the San Francisco Mint, wrote a report recommending that the U.S. Mint produce a commercial dollar for export to East Asia that would compete with other countries’ coins of this type. His reasoning was that most of those coins would be hoarded or melted in Asia and never redeemed, which would create a large seigniorage profit for the U.S.

Of significance is the fact that after this proposal became the basis for legislation, a Department of Treasury agent named Henry Linderman suggested that the coins did not need to have legal tender status and could simply be similar to silver bullion bars that have their weight and fineness stamped on them. Many numismatists today believe it would have been far preferable if the coins had remained silver bullion and not legal tender, especially given their later reception in the U.S.

As these ideas were crafted into the Coinage Act of 1873, the House of Representatives proposed a heavier silver dollar with a weight of 420 grains (27 grams). But then Congress instead voted that a standard silver dollar with the same weight as the existing coins of 384 grains (24.9 grams) be minted, but the Senate had that changed back to the heavier coin, which is what was actually enacted and why the Trade dollar is larger and heavier than other U.S. silver dollars.

In addition, at the last minute the coins were given legal tender status up to $5 and inscriptions were added to the reverse indicating their weight and fineness, which Chinese merchants were not able to understand.

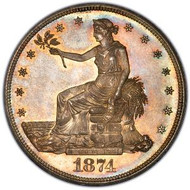

The design of the new Trade Dollar first minted in 1873 was created by Chief Engraver Charles Barber and featured on its obverse a motif with Liberty as a seated figure resting on a bale of merchandise facing to the viewer’s left, which was the direction of East Asia, while the reverse featured a bald eagle holding three arrows and an olive branch.

History of Trade dollar

The coins were minted from 1873 to 1878, but were only legal tender status until 1876, and after 1878 they were only made in small quantities and struck in Proof for inclusion in sets. The Proofs of 1884 and 1885, whose origins are not clear, are among the greatest rarities of 19th century American coinage

Chop marks are Chinese characters that were added by Chinese merchants to the coins most likely to test their authenticity, and some coins received multiple such marks as they passed from one merchant to another. Today, the coin is very popular with collectors, and mint state examples are scarce and expensive. Even nice circulated examples are not plentiful in the current market.

The coin was also widely counterfeited, especially in China using base metals, so buyers should be careful about acquiring examples that have not been professionally graded.

From 1873-1878, the Trade dollar became increasingly popular in China with demand for the coins rising, and they were by this time worth a 2% premium over silver Mexican pesos. Meanwhile, U.S. silver imports during this period declined sharply. By 1875 the coins had essentially replaced the Mexican ones in Asia.

But back at home, as Eric Brothers explains, the coins became a punching bag in domestic disputes over silver and a bimetallic monetary system. Silver advocates saw it as a threat, while those who favored a gold standard though the Trade dollar proved that a bimetallic system could not work.

The coin became very unpopular within the U.S. where they began appearing in commerce in 1874 because plummeting silver prices pushed its value down to 80 cents. Many banks and businesses refused to accept them and those that did such as in western states set their own fixed, lower value on the coins.

Yet after they were demonetized in July 1976, the coins continued to circulate in the U.S. because silver bullion producers continued to have their silver coined into Trade dollars. Finally, in 1887 the law authorizing them was repealed, and all coins that were not damaged with chop marks were redeemed by the Treasury, making them the only U.S. coin rever recalled by the government.

After the coin’s demise, more countries created their own trade dollars such as the French piastre de commerce in 1885 and the British trade dollar in 1895 in addition to those that already existed such as Japanese trade dollar. The U.S. had to resume importing Mexican silver coins at a premium for trading purposes.

Sources:

Eric Brothers, “The United States Trade Dollar: A Rousing Success,” The Numismatist, February 2022, pages 30-38.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_dollar_(United_States_coin)